One has a fight song from a 50-year-old Broadway show, another has students who have no music program supporting them. Why do they work as hard as the teams on the court even though the spotlight – and the TV cameras – seldom looks their way? “We’re here to sing, chant and play our hearts out!” says Villanova’s piccolo player Julia Maher

By NCPA staff

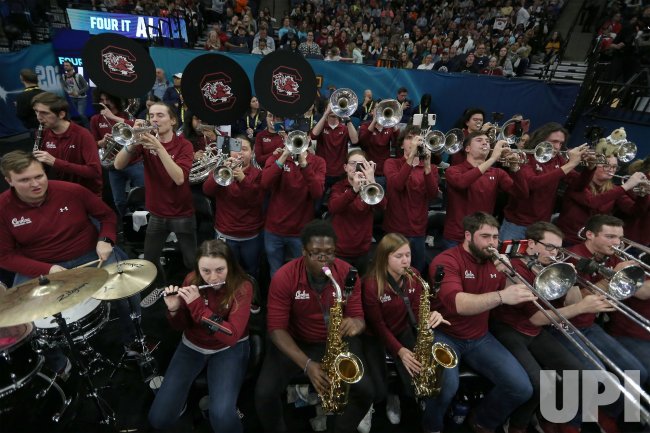

Shortly after the final seconds of the University of South Carolina Gamecocks championship win ticked off the clock and the women launched into celebration, Dr. Quintus Wrighten and his beloved Carolina Basketball Band (the Gamecocks’ pep band), unbeknownst to them, had their own “One Shining Moment” coming their way.

As one of only two universities with a Broadway show Fight Song, they blasted out “Step to the Rear” (adapted from 1969’s “How Now, Dow Jones”) for the Gamecocks team and fans. The game was the culmination of the NCAA Women’s Division I Basketball Tournament also known as March Madness. Earlier, during a Sunday morning interview, Wrighten guiltily confessed with a sly smile, “Nerdy moment…I actually woke up this morning with our fight song ringing in my head.”

During college basketball’s biggest weekend, when NCAA tournaments for men and women culminate in the frenzy of the Final Four, the spotlight is on the players and the coaches. It rarely focuses on the teams’ pep bands – the unsung heroes that pump up the fans’ adrenaline which in turn drives the players to win.

During college basketball’s biggest weekend, when NCAA tournaments for men and women culminate in the frenzy of the Final Four, the spotlight is on the players and the coaches. It rarely focuses on the teams’ pep bands – the unsung heroes that pump up the fans’ adrenaline which in turn drives the players to win.

But when it does (like in 2015 when Villanova’s Roxanne Chalifoux broke down in tears playing piccolo as her Wildcats lost), the emotions are fully on view and just as intense as those of the players on the court. And it’s just as intense for the pep band directors. The National Collegiate Performing Arts (NCPA)™ spoke to some of the band directors for the men’s and women’s teams in the final rounds to get their point of view.

Why shouldn’t these talented musicians share more of the glory? There are actually more college banders than ballers. Think 4,000 colleges with 50-150 band members each versus 1,300 basketball programs with 15 players – it roughs out to at least 150,000 pep banders compared about 30,000 ball players. And they work hard too: With rehearsals, individual practice and 1-2 games a week, the 5-20-hour weekly commitment – often year-round – exceeds that of many varsity sports. That’s why the NCPA was founded – to empower the nation’s diverse collegiate performing artists to compete for their own national championships, and with the same levels of glory and pride as the athletes. An NCAA for college performing arts. But guess what, they also know basketball, their passion evidenced by sneaking risky looks over their sheet music on their music stands at the action on the court.

Over in the men’s division, where the University of Kansas won the championship Monday night, Sharon Lee Toulouse, the school’s Assistant Director of Bands and director of the school’s pep band said, “I know we’re not the ones on the court, on the field of battle, but my band is all in. They’re invested…emotionally tied. I was so immensely proud of their dedication, devotion and tenacity. Sometimes they are the only “student body” at these games, and they know the team needs that energy and they BRING IT!” The band directors turn out to be as diverse in background, career path and temperament as the media-monopolizing hoops coaches are.

Kansas beat Villanova on Saturday to reach the championship – and it was a rare matchup of female band leaders – with Beth Sokolowski leading Villanova and Toulouse directing Kansas. Toulouse played trumpet at Kansas in college and went to the Final Four her freshman year, so the excitement this year is mirroring some thrilling memories.

For her part, Sokolowski “Pepped for” Temple University’s relentless Hall of Fame basketball coach John Chaney before migrating to the more subdued Main Line environs, and Jay Wright’s positive-attitude coaching demeanor, in Wildcat country. What she wants everyone to know is that Villanova has no music program, so these students aren’t working toward degrees, receiving stipends, or anything like that.

Julia Maher, a piccolo-playing senior in the band supports this saying, “We play music because we love music, we grow together as a family and community. We all sign up for band camp and form amazing bonds and have fun.”

“They do it only for the love of music. It’s their avocation,” says Sokolowski.

The University of Connecticut’s (UConn) Ricardo Brown’s dynamic presence hardly fits the band leader stereotype: He will finish his doctorate this summer and also was a high-school wrestler. His strong family instilled in him the importance of education and music and he was one of only four people from his humble community in Portsmouth, Virginia who went to college – and three of those four were from his family. He prides himself on making what the band does “cool,” he said.

“I want everyone to come to a UConn game, and no matter where they’re from they can relate to the music and party,” said Brown.

Contrast that energy with the University of North Carolina (UNC) – Chapel Hill’s Jeff Fuchs and his executive’s demeanor. He was at the Championship here for his 11th time – he’s been doing this since 1995 and has worked with more than 3,200 students over the years. But his enthusiasm can’t be hidden behind all that experience. About this year’s semifinals where they beat Duke, he said, “I’m not sure if the Second Coming has to happen to generate the level of excitement we had over that game!”

One of his band members Sean Raycroft may have said it best, in a way every striving musician can relate to: “Who would have ever thought that playing the mellophone was my key to getting courtside seats to one of the biggest college basketball games of all time?” Jeff Au, the director of Duke’s marching and pep bands agrees, even though UNC-Chapel Hill knocked out his team in the semifinal. It’s his third Final Four, but he says the game against UNC-Chapel Hill was the “National Championship game of all time.” Au, who played trumpet when he was at Notre Dame, says he brings a ton of current music with a lot of energy. His slogan is “Always Be Tuning,” and of his job he says, “I am living the pep band dream – nowhere else can I have this experience.”

The one thing there isn’t among any of these band leaders, is a Bobby Knight-type, the profane college basketball coach known for throwing chairs on the court, or more appropriate, a Terence Fletcher, the terrorizing band leader in the Oscar-nominated “Whiplash” film played by J.K. Simmons.

And just like the Final Four story lines on the court, the bands have story lines. Recently retired UNC-Chapel Hill coach Roy Williams moved from Kansas to UNC-Chapel Hill, just like Kansas band leader Jeff Fuchs did to take over the Marching Tar Heels band five years ago. Similarly, basketball coach mentee Hubert Davis took over for Williams at UNC-Chapel Hill when he left, just like Kansas band leader Toulouse took over for her mentor Fuchs when he departed.

Just before the semifinals, Toulouse speculated about both Kansas and UNC-Chapel Hill winning, so that she could share center court with her mentor Fuchs in a “dream final” in front of the crowd of 76,000. Note she said “with” not “against” – the profession thrives on a collegial mentality.

The pinnacle of the pep profession is this Final Four big stage, and with a maximum of 29 pep band members allowed by the NCAA for the eight Final Four teams, only roughly one in 500 pep band members might experience a Final Four and one in 2,000 a Championship.

UConn’s Brown points out another thing most people probably never think about: The students aren’t just representing teams and schools, but they’re the pride of their entire cities, their entire states.

“The way these band students over the last year have performed and represented themselves and represented the school and represented our state, I couldn’t be more proud,” Brown said.

And there are some perks. Sokolowski says her band has been traveling non-stop for six weeks at this point. Utterly grueling, but on the other hand, she says they are enjoying “rock star status.” They stay at the same hotels as the athletes, and get the same applause when they walk through the lobby.

And there are some perks. Sokolowski says her band has been traveling non-stop for six weeks at this point. Utterly grueling, but on the other hand, she says they are enjoying “rock star status.” They stay at the same hotels as the athletes, and get the same applause when they walk through the lobby.

Toulouse, still basking in the Kansas victory two days later, thinks that sense of pride will last their whole lives. “As I reflect, I want to tell my band to cherish these moments!” she said. “When you’re in your 50s, you’ll look back on these moments and be forever thankful you chose to do this.”

So, as the courtside celebration raged and Wrighten’s giddy Gamecocks gang, trumpeters to trombonists, clarinetists and piccoloists, and a mellophonist or two for good measure, bursts at the seams of the boundary keeping them from the hardwood, their “One Shining Moment” happened. As South Carolina Gamecocks coach, Dawn Staley, circled the arena with the trophy, she suddenly stopped, facing the roped-in “Peppers,” and in front of 5 million viewers (the record for a women’s championship in 18 years), handed her team the championship trophy, with an appreciative look that said, “Thank you, this is for you too!”

The National Collegiate Performing Arts (NCPA)TM

The NCPA is dedicated to organizing, elevating and empowering the fragmented 2 million college performers (500,000+ groups, 25+ genres) by creating increased structure to provide competition and marketing opportunities similar to those available to the 480,000 NCAA athletes (25,000 teams, 20 sports) to represent their University competing for national championships, glory and pride, as part of a cohesive NCPA community.

UpStaged Entertainment Group

UpStaged is a NYC-based, diversified performing arts platform empowering the world’s student performers to compete for live/digital national championships, like student athletes, across more than 20 genres (e.g., step, comedy, a cappella) in premier venues and on virtual platforms, from Lincoln Center to Zoom, operating under its NCPA and National High School Performing Arts (NHSPA)TM brands. More information at Upstagedu.com.